Ben Recht got my attention with a tweet about his blog post "The Higgs discovery did not take place.” I’m generally a fan of Ben’s writing, but I think he’s off base on a number of issues, and I’ll explain why. [Updated Oct 23rd, 2024]

Ben's post starts off with a debate about statistics (the role of null hypothesis testing), but the post goes into a lot of other issues and ends with a damning conclusion

The Higgs Discovery is a celebration of modern bureaucracy, not a revelation about material reality.

Along the way, the post meanders through many important issues and questions:

- The complexity of particle physics – does anyone actually understand what’s going on?

- Is the Higgs "real" or relevant to our everyday lives?

- Issues of trust in science

- Criticism of bureaucracy and big science

While I agree with some of the points and could quibble about some others, there are a few important points that are just flat out wrong or that I disagree with. Where to start?

Do you need to understand all the fancy theory to be able to claim the discovery? Does anyone actually understand what’s going on?

Ben’s post spends a lot of time talking about how complicated particle physics is – both the theoretical framework of quantum field theory and the complex experimental apparatus. He’s right that these are very complicated, and he’s not wrong to be skeptical.

The point is that physicists are also very skeptical about these things. That’s part of the reason why in the initial search for the Higgs at the LHC, there was a lot of emphasis on keeping things as simple as possible. For example, some people wanted to use machine learning to add sensitivity and expedite the discovery, but it wasn’t necessary for the discovery. The teams advocated for simpler, more robust, easier to understand methods for the initial discovery.

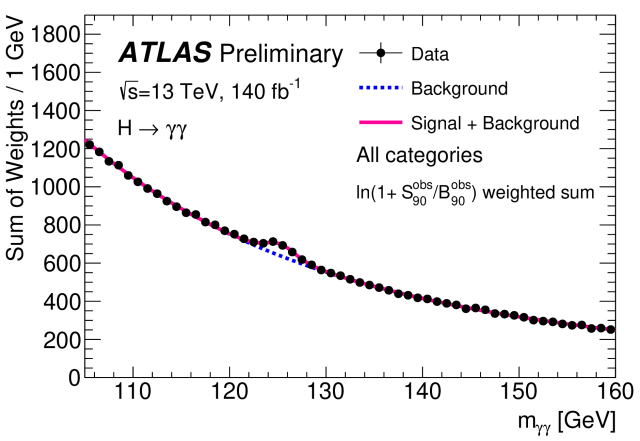

One of the two main searches for the Higgs was ‘data driven’ with only a loose connection to theory. The null and alternate hypotheses were not built upon the edifice of quantum field theory, instead it was a very pedestrian statement that under the null hypothesis, a certain distribution should be smoothly falling, while the alternate hypothesis would have an additoinal bump corresponding to a new particle. Here's what the plot looks like today... do you see the bump? (insert, yes I see the bump emoji)

This bump is what physicists call a resonance. It follows directly from energy and momentum conservation and special relativity that we teach first year undergraduates (hardly the ivory towers).

This bump or resonance is intimately tied to what physicists mean when they say ‘particle’. If you dig a bit deeper, the term resonance is also tied to one of the most elementary physical systems: the simple harmonic oscillator. Sure, when you treat these things quantum mechanically, it gets more sophisticated, but my point is it doesn’t require highfalutin mathematics and quantum field theory to say that we discovered a new particle at the LHC.

Now if you want to say that the particle we saw is the Higgs boson it’s a bit more complicated. Even without reference to the fancy theory, we can say that it has some of the properties that we expect, for instance it’s a “spin-0” particle (basically meaning that it decays isotropically).

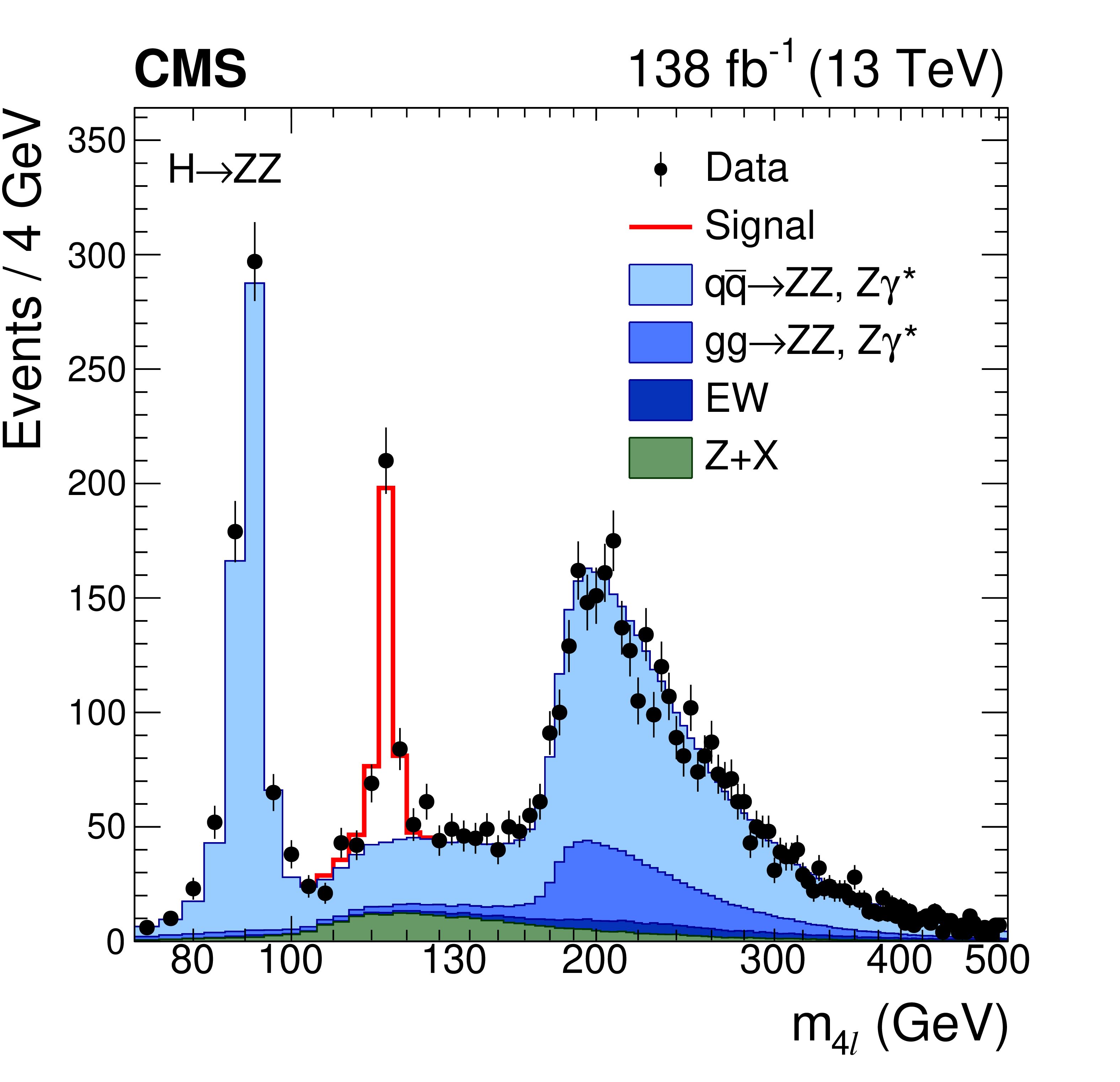

There are other ways to search for the Higgs where it decays into different particles. Again you get a bump. In the example below the alternate hypothesis is a bump on top of the ‘background’ and the null hypothesis is ‘background only.’ In this case, the background isn’t just a smoothly falling distribution, and this search relies more heavily on our ability to predict the background using theory and simulations of our detectors (blue and green). But I think everyone would agree that the data (black dots) don’t follow the null (stack of blue and green) distribution and it clearly prefers that alternate hypothesis with the additional red bump. What's the Poisson probability that you get more than 200 events in that bin when you expect ~40 under the null distribution? We do calculate it, including nuisance parameters and systematic uncertainties and all that jazz, but who cares, it's astronomically small.

These are more recent results with a lot more data, and the statistical significance is WAY beyond \(5\sigma\). If you don’t like frequentist statistics, you are free to calculate your Bayes factor or any other statistical measure you want. There is no scale used in any area of science where this wouldn’t be a slam dunk in favor of the alternate hypothesis.

Without any fancy theory, you can say that if there is one particle producing both bumps, then I should expect the bumps to show up at the same place (around 125 GeV). That’s indeed the case. And both the ATLAS and CMS experiments saw this bump in the same location (here's the ATLAS plot).

So when Ben writes “Do we believe that their presented statistical counts represent a close enough facsimile of experimental conditions to corroborate an ornate, impossible to understand theory?” I hope you can see how that is off base when it comes to claiming discovery of a new particle. It's less off base when it comes to connecting this discovery to the underlying theory of the standard model of particle physics.

Now what the theory allows you to do is go further and say very precise things about how to relate these two plots. For example, you can say how high you expect each of these bumps to be if the Higgs boson of the Standard Model is responsible for them. And guess what… that all checks out. Here's a recent summary from the CMS experiment of those checks.

It's worth nothing that the experiments were slow to say in scientific papers and formal presentations that we had discovered “the Higgs”. The experiments initially said we discovered “a particle” in the search for the Standard Model Higgs. It took about a year of checks before the experiments started referring to this new particle as “a Higgs” boson, leaving room for the possibility that it might not be the Higgs of the standard model, but a particle that plays the same role in a slightly different theory. In fact, this is the bulk of Higgs physics today, to stringently test if this particle deviates in any way from the standard model’s predictions.

Is the discovery just modern bureaucracy?

The article post that the big experiments operate by majority vote. That’s laughable and misleading. First, the majority vote framing evokes Tyranny of the majority and makes it seem like there is a significant fraction of the particle physics community that doesn’t agree that we discovered the Higgs.

In reality, we operate on consensus, which can be slow and, at times, frustrating. If individual people are not convinced, they can effectively block the collaborations from making claims they don't agree with. That rarely happens, but the emphasis on consensus leads to a slow process that tends to be very careful and conservative. You’d be hard-pressed to find a practicing particle physicist (among the ~10,000 working in this field from all around the world) that isn’t convinced that we discovered a particle in the search for the Higgs.

There are a few that argued early on about whether or not what we found is the Higgs boson, but that quickly becomes a much more subtle question. I’d say that the overwhelming consensus is that a) we discovered a particle, b) that particle has the properties to be considered “a Higgs boson”, c) it is consistent with the specific properties we expect for the Higgs boson found in the Standard Model, and d) we are doing lots of precision measurements to see if we can uncover any deviations from the Standard Model that might point to some kind of new physics.

Is the Higgs relevant?

This part is not about statistics, but physics and impact on our lives. Ben writes,

So I don’t care either way if physicists think they found a Higgs. It has zero bearing on my existence.

🤣 Ben, atoms literally wouldn’t form if the Higgs (or something like it) didn’t “give mass” to the electron!

There’s another way that the Higgs is relevant in our everyday life. The origin story conceptually for the Higgs actually has to do with radioactive decay and the weak nuclear force. That underpins nuclear power, nuclear weapons, carbon dating, chemotherapy, and a host of other relevant technologies.

The fact that all of this stuff about radioactive decay and nuclear physics is related to the mass of the electron and the existence of atoms is far from obvious. The power of quantum field theory is that it provides a conceptual framework that can relate these phenomena through a causal mechanism.

Ben writes “There has to be something we can do with substantive causal theories for them to be real.” Well one thing you can do with this causal theory is start with the observation that we have radioactive decay, follow a logical thought process heavily constrained by mathematical consistency arguments, and somehow predict that if you were to build the LHC that you will produce a particle that no one has ever seen before.

More specifically, you can predict that you should see a bump in a specific plot and what you would expect to see in hundreds or thousands of other plots. We did that. It took about 20 years to make it happen. Not only do we see what you would expect if the Higgs exists, we definitely DO NOT see what you would expect if it did not exist (i.e. the null hypothesis).

Why do you care if there’s a bump in some plot? Well you don’t really, but that’s the confirmation that this mechanism -- as opposed to some other one -- is what is going on. And understanding that mechanism is critical to unraveling the broader mysteries of how the universe works.

It’s true that you can describe chemistry and most quantum physics that we actually use in our daily lives without knowing if the Higgs mechanism is ultimately responsible for the mass of the electron or radioactive decay, but that is a shallow criticism that is basically saying that doing pure, basic research is a waste of time.

While it is true that basic science has led to many practical applications, that's not always true. The people studying quantum mechanics back in the 1920s were doing basic research that seemed very far removed from our lives. But that ended up giving us lasers, transistors, etc. Is the Higgs like that? I doubt it, but who knows. Personally, I am critical of physicists that try to make overly optimistic extrapolations of how the Higgs is going to directly affect any technologies. The case for impact on society is much more clear through spinoff technologies like CERN's role in inventing the world wide web or scaling up the production of superconducting materials for comercial production. But it's also important to realize that understanding the Higgs mechanism is sometimes a necessary ingredient for being able to understand other phenomena at the forefront of our understanding of the universe. It is quite possible that some downstream fundemental discovery that does end up having practical applications was only made possible because of what we learned about the Higgs at the LHC -- but no promises.

Can we trust this?

Let me start by saying that I think trust in science is a very important topic, and any scientific result should be met with a respectful level of skepticism. Issues of p-hacking are real. Pre-registration is important. I’m a big believer in open science, open data, etc. Ben’s post raises these important questions, although with some judgemental language that certainly hints at distrust and is probably a bit offensive to many of my colleagues.

Now to the second question. When we ask, “Does the Higgs Boson exist?” we are not asking about the material reality of an object. We're asking about our belief in a system. Do we believe that a collection of determined, over-credentialed scientists can organize themselves, through their democratic, participatory decision-making schemes, to decide upon the connection of data and theory? Do we believe that such institutions produce trustworthy procedures and rituals so that if they say they did something, then no one else has to check? Do we believe that their presented statistical counts represent a close enough facsimile of experimental conditions to corroborate an ornate, impossible to understand theory? Do we believe their committees properly adjudicate statistical practice and preregistration plans?

Where to start? The irony here is that particle physicists are very aware and concerned about these issues and we have some of the most stringent procedures of any scientific field that I can think of. Why? Partially because we rarely make discoveries, they are very expensive, and the field is very worried about making a false discovery claim.

First, let’s take on preregistration. Particle physicists are big on what we call ‘blind analysis’ where the data analysis procedure has to be approved before one looks at the data that is going to be used to make the final inference / conclusions. In addition, the general strategy for these searches were developed for decades.

Then there’s the phrase “no one else has to check”. It is tradition in our field to have two independent experiments for confirmation. (You can quibble about how independent they are, but the point is that it’s deeply ingrained in the culture of particle physics that these things could go wrong, so we’ve built a number of protective measures to avoid those problems.)

In addition, the major experiments have started releasing statistical models and open data. Recently, CMS released the statistical model and the data for the Higgs discovery as Open Data.

Don't take this literally, p-hacking and the look elsewhere effect

Particle physicists worry a lot about multiple testing. We call it the look-elswewhere effect, and we account for it / correct for it. We make the distincition between "local significance" and "global-significance" (that includes the correction).

The blog post quotes a Science magazine piece, which introduces some confusion and has this quote

For example, a 5σ significance tells us that the probability of the background alone fluctuating up locally by the amount observed or more is about 1 in 3 million. In particle physics, this criterion has become a convention to claim discovery but should not be interpreted literally.

Ben reacts strongly to this, which isn't totally unreasonable given what is (incorrectly) written in that Science Magazine article.

As far as I can tell, that Science Magazine glossary was written by Science Magazine, not by the experimental collaborations. Whoever wrote it, they confuse different things. \(5\sigma\) is just a different way to refer to a specific probability or p-value, it has nothing to do with if it's local (no correction for multiple testing) or global (with correction). When we claimed discovery, we had \(5\sigma\) globally in two independent experiments. These days it's way more significant than that.

Secondly, I don't know what they were thinking when they say it shouldn't be interpreted literally. We very much calculate these p-values based on the distribution of the profile likelihood ratio test statistic. We explictly correct for multiple testing. And we've also gone through the process of calculating Bayesian posteriors etc. using the same statistical model. It all matches up. I think the point there was that when the p-values get this small the specific numerical value of the p-value isn't that relevant. The same could be said for a Bayes factor.

So no, particle physicsist are not p-hacking. Moreover, when p-values get this small (\(<10^{-6}\)), it doesn't make a very big difference for the number of "tests" we are doing as we scan over the unknown Higgs boson mass (\(\approx 100\)). It's like a difference between \(5\sigma\) and \(5.1 \sigma\).

While it is in the weeds, the figure that Ben shows is not the figure that we use to claim we discovered the Higgs, this is. He writes "See the bump that goes outside of their green error bars? That’s the Higgs Boson. (insert shrug emoji)." That's just wrong. Ben links to this review by David van Dyk (a statistician that is engaged with the physics community, but not part of the experimental collaborations). Figure 5 of that review is the more relevant one. The next section in that review discusses how we correct / account for the look-elsewhere effect (aka multiple testing).

Mindless conventions

Yes \(5\sigma\) is just a convention, no one is (should be) defending that. But it's kind of irrelevant, the statistical significance here is rediculously high on any scale. I do share some of Ben's thoughts about the role of statistics and fairly arbitrary thresholds for providing compressed, crisp rules.

Interestingly, the field doesn't just go by these conventions. Not long ago there was an excess of events that was unexpected and by most statistical measures was very signficant. The field did not claim a discovery. Partially that's because the look-elsewhere effect was a significant penalty. But even then, it was quite significant. In essence, the field didn't claim a discovery because it was so unexpected and hard to reconcile with other things we would expect to see based on our understanding of quantum field theory. In the end, with more data that bumpt went away. If there's a criticism there, I think it's that the field did not rigidly abide by the mindless convention.

Now going back to the original question / debate at the start of the article, "What are the grand discoveries that we wouldn’t have made without an understanding of null hypothesis testing?" That seems like a weirdly worded question. It's more that the search itself naturally lends itself to a hypothesis testing framework. We literally have two competing hypotheses. That framing of the question has nothing to do with the arbitrary cutoffs for when you claim discovery or not. In this case, the evidence is so overwhelming, the cutoff is pracitcally irrelevant.

The irony of how the large particle physics experiments actually work

As mentioned above, the collaborations effectively work by consensus. Yes, there are too many meetings. Yes there is too much bureaucracy. If anyone knows how to get thousands of scientists employed by different institutions from all around the world to do this kind of cutting edge science more efficiently, please let us know.

The irony is that it's actually very hard to push through new ideas. The decision making process tends to only allow for more traditional / less fancy approaches. This is good for robustness and making sure everyone understands what's going on, but this actually drives a lot of young smart people away from the field.

Complex systems, engineering, and scale

Much of Ben's argument seems to be that particle physics is so complicated, no one understands it all, so you can't trust anything. This is a bit ironic coming from a professor in an engineering department. So much of our modern life is filled with very complicated systems composed of many components that no one person fully understands.

Does anyone understand every aspect of a laptop from the quantum mechanics in the transisitors to the fabrication of the integrated circuits to the operating system to the software on top of it? In broad strokes, sure, but in the details, no! That doesn't stop us from building laptops that work well (unless you are trying to print).

So much of science is built on the separation of scales. The details of phenomena at one scale are not particularly relevant at a larger scale. Experts of phenomena at different scales can understand those independent components, and collectively we understand how to compose them together. This is the case in particle physics and many other areas of science.

The situation in biology is much harder and more extreme because it's more difficult to have a clean separation of scales and the phenomena are so much more intrensically complicated. But even then, would you say that the dsicovery of a vaccines or antibiotic did not take place because no one understands the full story from the atomistic level to the level of organs or epedimics? That seems silly to me.

What would be more interesting criticism?

This will need to be a topic of some possible future blog post, but there are many issues where there are interesting criticisms, subtleties, or extensions. Some examples:

- The null hypothesis (e.g. no Higgs) is actually not very well defined from a quantum field theory point of view in the Higgs search. This is subtle, but you can't just take out the Higgs and make sensible calculations (related to gauge invariance). There are alternate approaches that do make sense with no Higgs, but you are faced with various arbitrary choices. It gets very subtle from a theoretical physics perspective, and it's fascinating when you pair that with the philosophical questions around null hypothesis testing.

- Particle physics does have situations where the hypothesis are not so data driven and they rely much more heavily on the theoretical edifice of quantum field theory and our simulation of the complicated detectors. In these cases, the statistical models are implicitly defined by simulators is actually a very hot topic that blends classical statistics with modern deep learning. We often say that the simulators don't have a tractable likelihood function. This applies to frequentist hypothesis testing, confidence intervals, and Bayesian inference. Confronting these challenging situations is what motivated simulation-based inference, which is applicable to a host of scientific disciplines.

- Model mis-specification is a very important topic. The physics community has gotten pretty good at adding more flexibility to the model to accomodate systematic uncertainties and procedures for coping with those nuisance parameters, but dealing with the residual model misspecification is definitely an area where all sciences -- particle physics included -- can and should improve.